Part II: Value-Added Measures: Valuing Meaningless Data over High-Quality Instruction

The first article in our series of how Florida’s education policies are undermining student success focused on teacher pay. However, we know that there are many issues other than low pay that are driving Florida’s educators to leave the profession. The remaining articles in the series will each focus on a specific policy that has been detrimental to the teaching profession and to student success. We’ll continue our examination of these bad policies by looking at one of the most significant aspects of 2011’s Student Success Act.

There are many reasons that Florida’s educators have come to loathe the misuse and abuse of Value-Added Model (VAM) scores, but there is perhaps no more egregious misuse of this data than to force an entire school to be disrupted just a few days into the start of a new school year.

The Ledger in Lakeland ran an article that shows how VAM scores are routinely used in ways that have a detrimental impact on students and even entire schools. In the article, Polk County School Board member Billy Townsend points out,

“the situation is so ludicrous that the entire fifth grade at Griffin Elementary — a turnaround school that has received a D rating two years in a row — is now being taught completely by long-term substitutes. One of those substitutes taught at the school all last year and had the lowest Florida Standards Assessment scores of the fifth grade teachers.”

How did this come to happen? How is it that every single fifth-grade student at Griffin Elementary wound up being taught by a long-term substitute while teachers who had been rated highly effective were forced to transfer to another school?

The unfortunate answer is that the State Board of Education and the Florida Legislature have spent over a decade stripping school boards of local control. In particular, it is State Board Rule 6A-1.099811(8)(b)13 that caused the VAM-related disruptions at Griffin Elementary and other schools all over the state for the past few years.

This rule prescribes how school districts are to “turnaround” schools that have been deemed “persistently-low performing.” There are myriad hoops schools and districts must jump though in order to demonstrate their commitment to turning around a school including the need to document “how the district reassigned or non-renewed instructional personnel with a rating of Unsatisfactory or Needs Improvement, based on the most recent three-year aggregated state VAM…”

When the State Board substitutes their wisdom over those who actually work in schools and know the names of the students, the ultimate consequence is that students suffer.

We would be remiss if we didn’t end this section by noting there are charter schools that meet the statutory definition of “persistently-low performing;” however, charter schools are exempt from this statute and therefore don’t have to disrupt their entire school based on VAM scores the way that public schools do.

A Primer on VAM

At this point you might be wondering, what even is a VAM score?

VAM is an attempt to calculate how much an individual teacher has contributed to the “growth” of their students’ test scores over the course of a school year. It is important to note that there are several different VAM formulas in use across the nation and the American Statistical Association cautions that “VAM scores and rankings can change substantially when a different model or test is used.” The VAM model currently used in Florida is pictured below. The definition for each term in the below model can be found on page 9 of this document.

Specifically, what VAM scores currently measure in Florida is “growth” in these areas:

- English Language Arts in grades 4-10 as measured by the Florida Standards Assessment (FSA)

- Math in grades 4-8 as measured on the FSA

- Algebra I End-of-Course (EOC) Exam in grades 8-9.

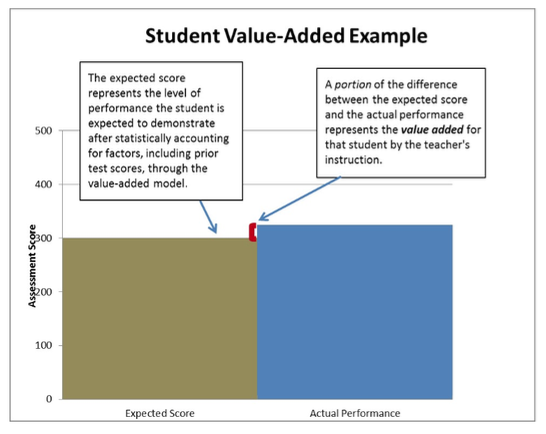

Each student who is enrolled in one the above courses and has a test score from the prior year is assigned an “expected” score for the current year. (It should be noted their expected score is not known until after their test has already been scored. You read that correctly, their test is scored and then it is determined how they were expected to have performed. Makes perfect sense, right?)

The student’s expected score is then measured against their actual performance. To the extent the student performs better than expected, the teacher is credited for having contributed positively to the student’s growth. Similarly, to the extent the student performs worse than expected the teacher is blamed for having contributed negatively to the student’s growth.

Here is a graphical representation of VAM as provided by the Florida Department of Education.

Since VAM scores are based on standardized test results, the only “growth” that is measured is that which can be measured on a standardized test. A VAM score, for instance, is unable to measure growth in areas like creativity, critical thinking, social and emotional intelligence, tenacity, teamwork, or many other skills that differentiate students from robots. Some of the skills that will matter the most to any individual student’s future success in life aren’t even pretended to be captured in VAM.

As we’ll demonstrate below, even the skills that VAM purports to capture are not effectively nor consistently measured by the formula.

VAM is Unquestionably a Scam

Even if they don’t know the name Educational Testing Services (ETS), most Floridians are aware of the tests they produce and administer including the Graduate Record Exam (GRE). One of the tests ETS administers – the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)– is often touted by Florida’s lawmakers and state board of education members as showing evidence of the tremendous success that Florida has achieved over the past two decades.

Yet those same individuals turn a blind eye to what ETS has to say about VAM. VAM scores are highly volatile from year-to-year,

“Typically, only about a third of 1 year’s top performers were in the category the following year, and likewise, only about a third of 1 year’s lowest performers where in the lowest category the following year.” (p 18)

And it is not just year-to-year VAM scores that are highly volatile. Teachers who teach multiple courses associated with a VAM score can have widely varied scores. The Florida Times-Union tells the story of a teacher who was “blown away” to discover “her sixth grade English language arts VAM score of negative 131.5 percent. On the other hand, her eighth grade VAM score was a positive 19.2 percent.”

While one might reasonably expect that an individual English teacher might be more effective at teaching eighth grade than sixth grade, it defies logic to believe that the teacher could have a value of -131.5 to one group of students and a value of 19.2 to another. Whatever it is that the VAM score is measuring, it is clearly not a measure of teacher effectiveness.

That is one reason why the ETS has weighed in on whether or not VAM scores should be used in personnel decisions. Not surprisingly, they disapprove of the practice:

“Teacher VAM scores should emphatically not (emphasis in original) be included as a substantial factor with a fixed weight in consequential personnel decisions. The information they provide is simply not good enough to be used that way.” (p 23)

Now seems like a good time to remind you that while the single largest educational and assessment organization in the world cautions that VAM scores shouldn’t be used in “consequential personnel decisions,” students at Griffin Elementary lost a highly effective teacher to be replaced with a long-term substitute because of the Florida State Board of Education’s unwavering faith in VAM.

The unelected members of Florida’s board of education would likely point out that they attempt to mitigate VAM’s flaws by using a three-year average VAM score. But, this too, is addressed by ETS:

“Some of these concerns can be addressed, by using teacher scores averaged across several years of data, for example. But the interpretive argument is a chain of reasoning, and every proposition in the chain must be supported.” (p 23)

The American Statistical Association (ASA) released a statement which further illustrates this point especially when VAM scores are used to make high-stakes decisions for specific types of schools such as those the Department of Education deems persistently low-performing. In part, the ASA’s statement reads:

“Multiple years of data, however, do not help problems caused when a model systematically undervalues teachers who work in specific contexts or with specific types of students, since that systematic undervaluation would be present in every year of data.”

These are the very types of systemic undervaluing that the ASA warns against.

If the State Board of Education created a new rule that stated teachers in a turnaround school would have to be transferred if they wore red on Wednesdays, they would be rightfully condemned; nobody in their right mind would argue that the color of one’s shirt is related to their effectiveness as a teacher. Public pressure would likely force the board to reevaluate and ultimately rescind the rule.

The same thing must happen with regards to VAM; while it has the pretense of accuracy by way of its mathematical equation, it should be clear by now that a teacher’s VAM score is no greater of an indication of their teaching ability than what color clothes they wear.

Faux Accountability for Teachers, No Accountability for Policy Makers

We are not now, and never have been, afraid of teacher accountability.

However, we cannot tolerate the current definition of accountability in Florida which insists on placing so much emphasis on things that matter so little such as VAM scores.

We cannot tolerate a system that only purports to care about student success while simultaneously wreaking havoc at schools like Griffin Elementary.

When over 300,000 students started this school year without a highly qualified certified teacher in Florida, that was not a failure of teacher accountability. That is a failure of Tallahassee bureaucrats to create a system that demonstrates respect for its educators.

When students attend schools with more police officers than counselors and nurses, that is not a failure of teacher accountability. That is a failure of Tallahassee bureaucrats to invest in students’ safety and well-being.

When students attend schools that do not have functioning air conditioning, much less adequate funds for music, art, science materials, and even basic supplies such as pencils and paper, that is not a failure of teacher accountability. That is a failure of Tallahassee bureaucrats who have spent so much time focusing on data they have lost complete sight of the learning conditions of the students they are supposed to serve.

When local control has been eroded to such a degree that five unelected members of the state board of education are able to override what a school principal and district superintendent think is the best placement for a teacher, that is not a failure of teacher accountability. That is a failure of Tallahassee bureaucrats to acknowledge that they do not always know best for each of Florida’s 67 counties.

As Florida must rethink its accountability system, it must also rethink the bonuses that have become an integral part of the system. As we documented in Part I of our series, bonuses have not worked. We predicted they would not, as did ETS in 2013 when they wrote,

In the most successful schools, teachers work together effectively. If teachers are placed in competition with one another for bonuses or even future employment, their collaborative arrangements for the benefit of individual students as well as the supportive peer and mentoring relationships that help beginning teachers learn to teach better may suffer. (p 24)

Continuing to pit teachers against one another by offering bonuses for the performance of their students as measured by VAM scores is educational malpractice. There is no evidence to show these bonus schemes have helped student achievement. As Commissioner Richard Corcoran touts the upcoming legislative session will see “landmark” teacher compensation, it should be a given that any compensation tied to VAM will only be a landmark failure.

Re-Centering the Focus on Student Success

“Of course we should hold teachers accountable, but this does not mean we have to pretend that mathematical models can do something they cannot…In any event, we ought to expect more from our teachers than what value-added attempts to measure.” -John Ewing, Mathematical Intimidation: Driven by the Data

Ewing’s words are very much in line with the views of professional educators all across Florida and of the Florida Education Association.

Both of the national teachers’ unions, the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association have laid out in very specific detail what that should look like. The Florida Education Association is proud to be affiliated with both unions, and we support their frameworks for teacher evaluations which are centered on improving student learning.

Some of the hallmarks of both the above proposals include the following elements which must be a part of any accountability system that is focused on student success:

- Multiple measures

- Evaluator training

- Timely feedback

- Professional development

- Local control

It is time to end the chaos that VAM scores annually bring to students and schools across the state of Florida, and it is time to develop a new accountability system that values the growth and contribution of students and teachers as human beings and not merely what can be gleaned from students and teachers as datapoints.

Want more in-depth coverage of the ramifications of two decades of Bad Policy and Low Pay? Check out Part III of our series, which focuses on the destructive effects of Annual Contracts.